review

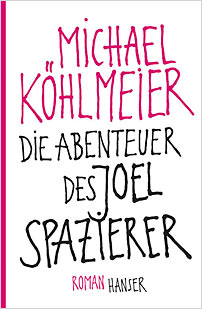

The Adventures of Joel Spazierer is a picaresque novel par excellence which pays homage to Tristram Shandy and Prokofiev’s Lieutenant Kijé, with a wry nod to Rabelais. The protagonist of Köhlmeier’s impressive work is a master chameleon who switches effortlessly between his many identities. Spazierer’s life is shaped by a series of major moments in recent history, which he in turn also influences: from Stalin’s death in 1953 and the Hungarian Uprising of 1956, to Cuba’s politics during the 1960s and 1970s, and life within the German Democratic Republic.

Born in Hungary into a German-speaking family, Spazierer’s childhood is marked by a deeply traumatic experience of abandonment, and the narrative hints that this may have triggered his subsequent addiction to half-truths and blatant fabrication. If we are to believe our less than reliable narrator, the family leave Budapest shortly before the 1956 uprising, finding refuge with a Professor of Egyptology in Vienna before building a new life in a small Austrian town. Spazierer is a beautiful child with chestnut curls, handsome features and a smattering of golden freckles. He exudes the quiet charisma of a ‘devil-angel’ – a dangerous sort of bewitchment. His power lies in his ability to listen with apparent rapt attention to those with something to tell, and in guessing the kind of answers they are expecting and which will suit him best

Spazierer spends many years in prison on a murder charge, firstly in Switzerland and then in Austria, where he seizes opportunities to perfect his gift for languages and to learn a trade as a motor mechanic. After his release, a young priest helps him find a job as a caretaker in a home for theology students, which adds to his array of ‘talents’ a flair for moral philosophy and theology. When he needs to leave Austria – on the eve of his wedding to Italian beauty and one-time Communist, Allegra – he passes himself off as the grandson of Ernst Thälmann, the leader of the Communist Party during much of the Weimar Republic, and gains entry to the GDR where he becomes a popular university lecturer in the Atheism division of the philosophy department.

This highly enjoyable romp of a tale ducks and weaves, goes off at tangents and ricochets back and forth between the present and the past as its devil-may-care narrator spins his yarns, offering a wonderful send-up of bureaucracy and human vanity.

All recommendations from Spring 2013