review

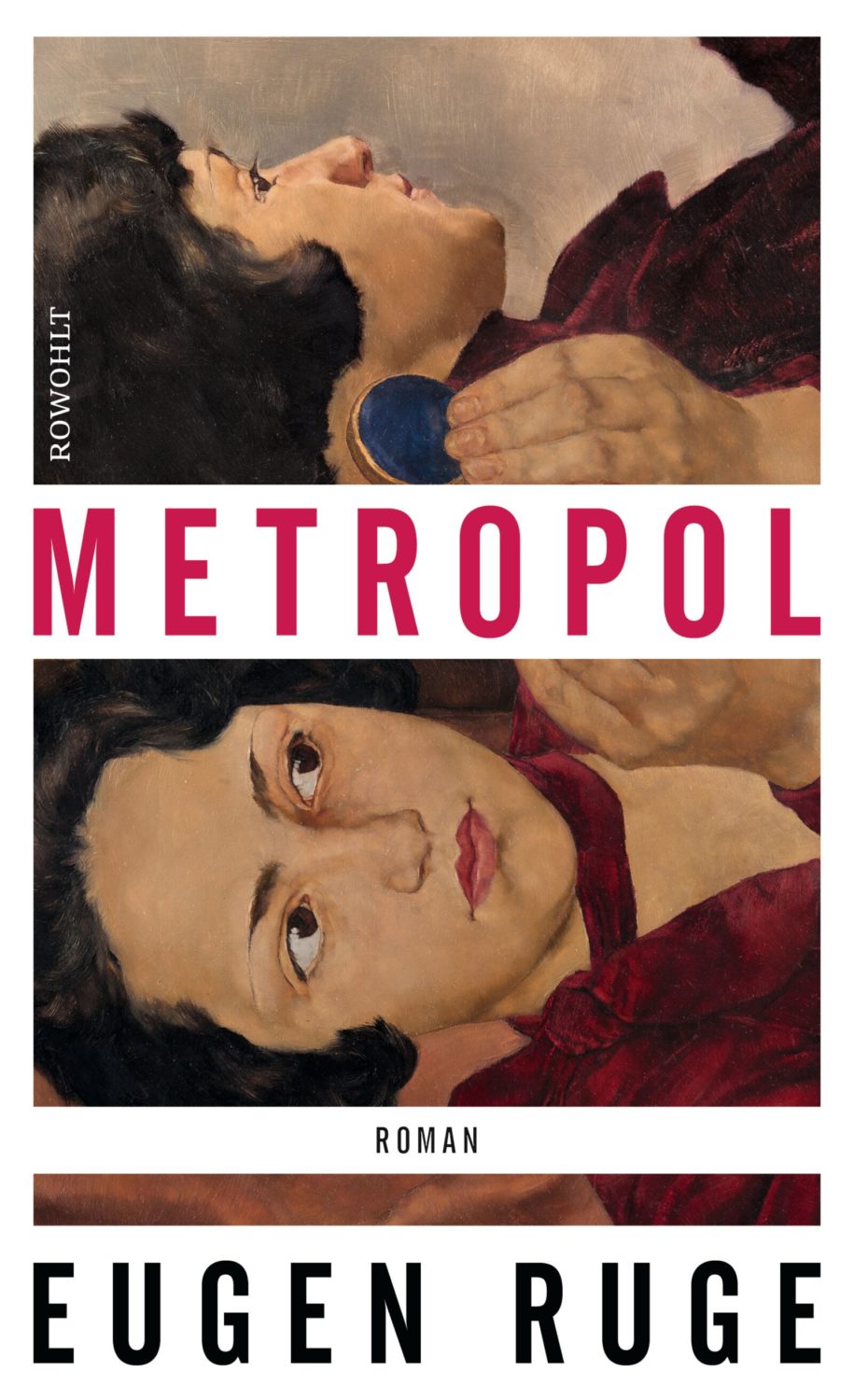

Hotel Metropol is a compelling take on a little-known chapter of Soviet history – and another outstanding novel from bestselling author Eugen Ruge, who won the 2011 German Book Prize with In Times of Fading Light.

Hotel Metropol is a novel constructed from real documents found by the author in his grandmother’s Russian secret service file. It is set during the purges of 1936–7 when his grandmother was part of a secret service unit that was later dissolved, with many of its members being put on trial. While waiting to hear if they would be arrested, the foreign staff mostly lived in one of Moscow’s smartest hotels. In its experimentation with the concept of fictionalising events using real documents, the novel plays into current debates in the English-language book market about the nature of truth in historical fiction.

The book opens with an account of Ruge gaining access to the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History in Moscow in order to read his grandmother’s file. The bureaucracy is almost nostalgically reminiscent of a socialist state and the narrative quickly moves back to 1930s Russia. The main narrative opens with the denunciation of Ruge’s grandparents, after which they lose their jobs in the Comintern’s secret service.

Having been dismissed, Charlotte and Wilhelm are resettled in a grand hotel, the Metropol, which is often referred to as a luxury prison. As the narrative progresses, more members of their unit are sent to join them and they learn of an increasing number of arrests and executions, often signalled by disturbing noises or absences at breakfast. Charlotte and Wilhelm become increasingly frustrated by their captivity, especially in the winter, when they are all but trapped in the hotel. Charlotte later gets another job and the novel reaches its climax with the arrest of their denunciator, Hilde Tal, and the signing of Hilde’s execution papers. In the novel’s epilogue, Ruge reveals which parts he has invented and meditates on the moral implications of fictionalising the story. He also divulges the fates of the characters in the book, explaining how his grandparents were fortunate to be allowed to leave the USSR without being sent to the Gulag.

Ruge’s epilogue is reminiscent of Hilary Mantel’s Reith Lectures and the author’s close personal connection to the story brings to mind a wealth of nonfiction writing from Thomas Harding to Philippe Sands and Mark Mazower, all of whom write about their families’ place in twentieth-century history.

All recommendations from Autumn 2019