review

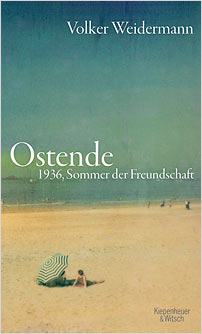

In 2008, Volker Weidermann published ‘The Book of Burned Books’, a fascinating study of the books burned by the Nazis, which focused particularly on titles by lesser-known authors. In Ostend he has turned his talents to better-known names, creating a brilliant portrait of the lives of a group of exiled writers in the Belgian seaside resort during a pivotal moment in twentieth-century history.

Ostend is subtitled ‘1936, Summer of Friendship’ and describes the extraordinary gathering of German and Austrian writers in the coastal city at this time, as they all apprehensively wondered about the outcome of those turbulent years of the mid-1930s. Stefan Zweig was staying in Ostend with his lover and secretary Lotte Altmann, and persuaded his friend Joseph Roth to join them. Weidermann suggests that Zweig was aiming to help Roth sober up because the Belgians allegedly took a puritanical attitude to spirits, but that any such attempt was doomed to failure. Particularly following the arrival of the Aryan anti-Nazi writer Irmgard Keun, who immediately fell for Roth and he for her. She was fond of the bottle herself, if less self-destructively than Roth. Keun was also a considerable literary talent and at least four of her books have modern English translations.

Roth and Zweig, then, are the two main friends of the subtitle, but they were joined at various times by figures such as Ernst Toller, Egon Erwin Kisch and Arthur Koestler. Weidermann’s book beautifully captures the friendship between Roth and the older Zweig, the outstanding features of their very different characters, and the seaside and café atmosphere of pre-war Ostend. As well as Nazi fascism, the threat of the Spanish Civil war was looming at the time. After that gathering in Ostend, writes Weidermann, Roth and Zweig ‘each […] went his own way. It was not a long one.’ Roth, ten years the younger, guessed ‘that his path would end earlier than Zweig’s’. And so it did, but not all that much earlier. After Roth’s death Irmgard Keun lived undercover in Germany and continued to write.

Ostend tells a sad but illuminating story, offering a perceptive account of evolving literary and social relationships, illustrated through a host of wonderfully entertaining anecdotes. Volker Weidermann is adept in bringing this endlessly intriguing episode of twentiethcentury cultural history to life, presenting fresh insights about some of German-language literature’s most significant literary voices.

All recommendations from Spring 2014