review

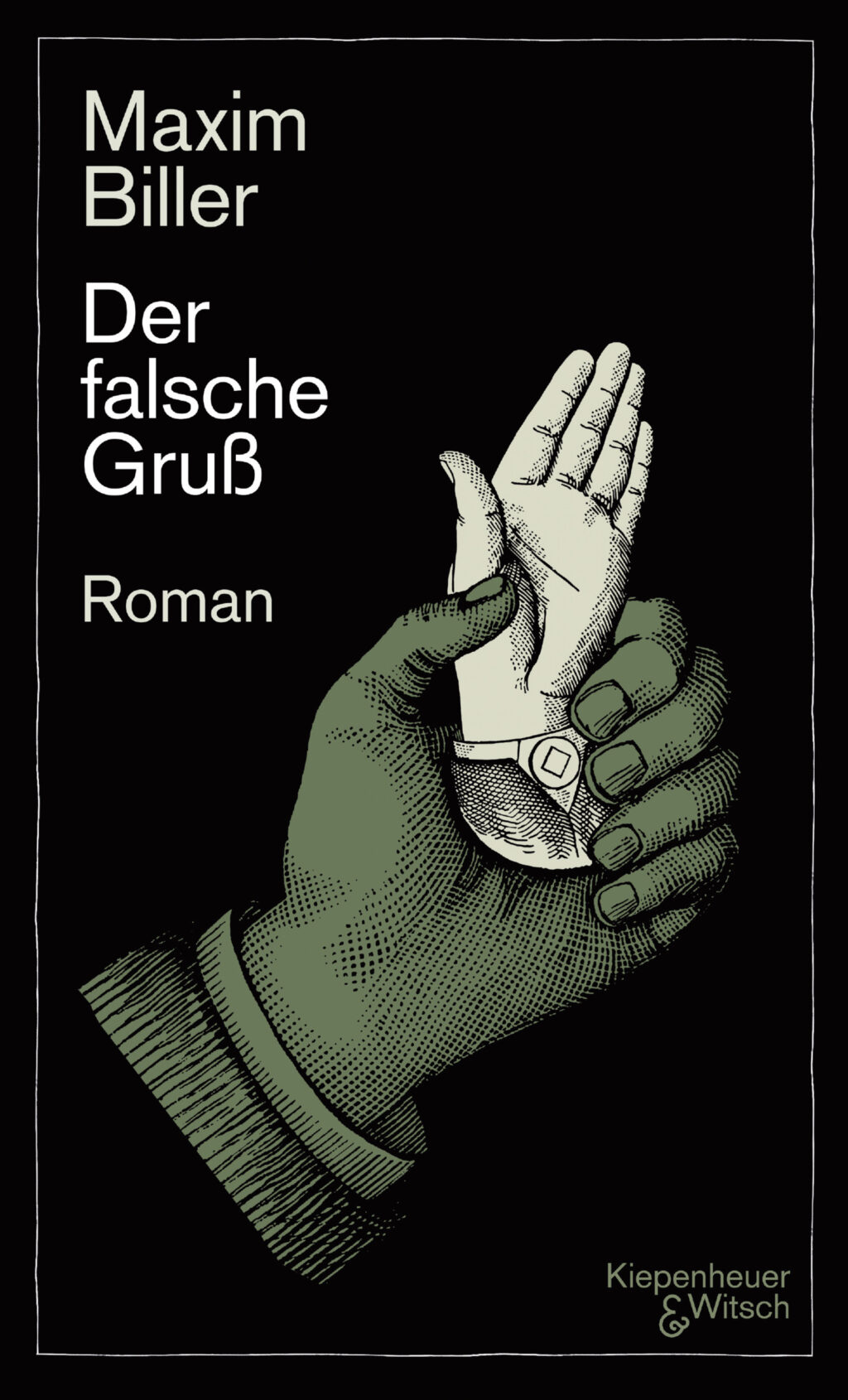

Intricate, complex and edgy, Maxim Biller’s The Fake Salute is a dark tale of ambition, envy and antisemitism.

Late one night, the acclaimed author Hans-Ulrich Barsilay is sitting in the Trois Minutes café with his glamorous entourage, when Erck Dessauer – himself an aspiring writer – marches up and performs a Hitler salute. Why on earth would he do such a thing? Erck, the unreliable, first-person narrator, claims Barsilay is a “trouble-maker and enemy of mankind”, and over the course of the novel he recalls his thorny relationship with Barsilay and his work.

Erck’s father, a professor in the GDR, had come home one day in the early 90s, furious about an article by Barsilay accusing East German Nazi thugs of stealing West Germany bit by bit. “There will always be them and us,” he had said to his son; subsequently, he killed himself. Years later, Erck reads the article in question and is startled to discover that Barsilay also attacks the West, taking this as proof of his perfidy.

It turns out that Barsilay is of Jewish origin, and Erck is quietly antisemitic. He is also a little in love with Barsilay’s sometime girlfriend, Valeria, whom he meets by chance as a student. Barsilay, arriving later at the same meeting, inquires after Erck’s family and career, and receives an excruciatingly detailed reply. Barsilay emphatically tells Erck he must write something original.

Later, Valeria pays Erck an accidental visit and they chat, but on catching him out in a lie about Barsilay she tells him she doesn’t want to see him again. Back in the Trois Minutes, Barsilay tells Erck that that was his moment – and he blew it.

Just a few days before the incident with the salute, Erck signs a contract for a biography of (the possibly Jewish) Naftali Frenkel, one-time prisoner of Stalin and later operator of the gulags. He is convinced that Barsilay, who has written a novella about the same figure, is envious of him, and is now glaring at him furiously across the café. He decides he must sabotage Barsilay, so as to sure up his own position. Yet in trying to scupper Barsilay’s career – for essentially antisemitic reasons – Erck has scuppered his own life chances at the same time. The reader only gradually realises how dangerous Erck’s apparent foolishness is.

This is a bold and original novel with echoes of Nabokov’s Pale Fire, and Biller is never afraid to pull the rug out from beneath his readers’ feet.

All recommendations from Autumn 2021