review

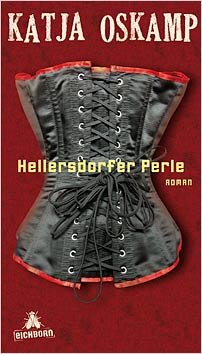

A woman, wearing nothing but a corset and boots, arms outstretched and handcuffed to a broomstick, stares at the audience from the stage. Later, she talks cryptically about her childhood, her desire to be dominated and her dream of world peace. The play, according to the theatre critic, is devoid of meaning. What possible relevance can a woman have for our lives when she allows herself to be handcuffed and prances fetishistically around the kitchen? Quite a lot, it seems, for the woman in the play is based on the critic’s partner of eight years. In this unusual and provocative new book from the award-winning author, we hear the story told from that woman’s perspective.

The narrator walks out on her partner Micha (the theatre critic) and their daughter and sets off into the Berlin night. In a shady pub, the ‘Hellersdorfer Perle’ (Pearl of Hellersdorf), she meets the Man, who buys her a drink and tells her to turn up the following evening in a skirt. This sets the pattern for their next few encounters during which the Man issues instructions which – to her own surprise – she follows enthusiastically. After a week (and the handcuffs scene that inspires the Man’s play), the narrator returns to Micha and resumes her middle-class life.

In the spirit of ‘keeping the romance alive’, she welcomes Micha’s suggestion of a night out at the theatre, unaware that the Man is the playwright. But after the play, ‘Pioneer of the Night’, the narrator leaves and begins her double life. By day, she is Paula’s mother and a hard-working copyeditor; by night, she dresses up and submits to the Man’s perverted demands. Finally she moves into an apartment near Hellersdorf, where she lives with Paula, and visits the Man for transgressive sex whenever Paula is away.

The Pearl challenges assumptions about femininity and relationships, telling the story of a woman who decides that relationships aren’t worth saving and that wearing a corset is more liberating than burning a bra. The conception of woman as mother or whore is recast in the figure of the narrator who chooses to become both mother and whore and who finds her independence by compartmentalizing these roles.

Sophisticated and very cleverly written, Oskamp’s new book succeeds in combining deeply uncomfortable subject matter – reminiscent of Nobel Laureate Elfriede Jelinek – with an extremely light touch. It will certainly cause a stir.

All recommendations from Spring 2010