review

A fascinating insight into a rarely discussed aspect of British relations with East Germany: BBC radio.

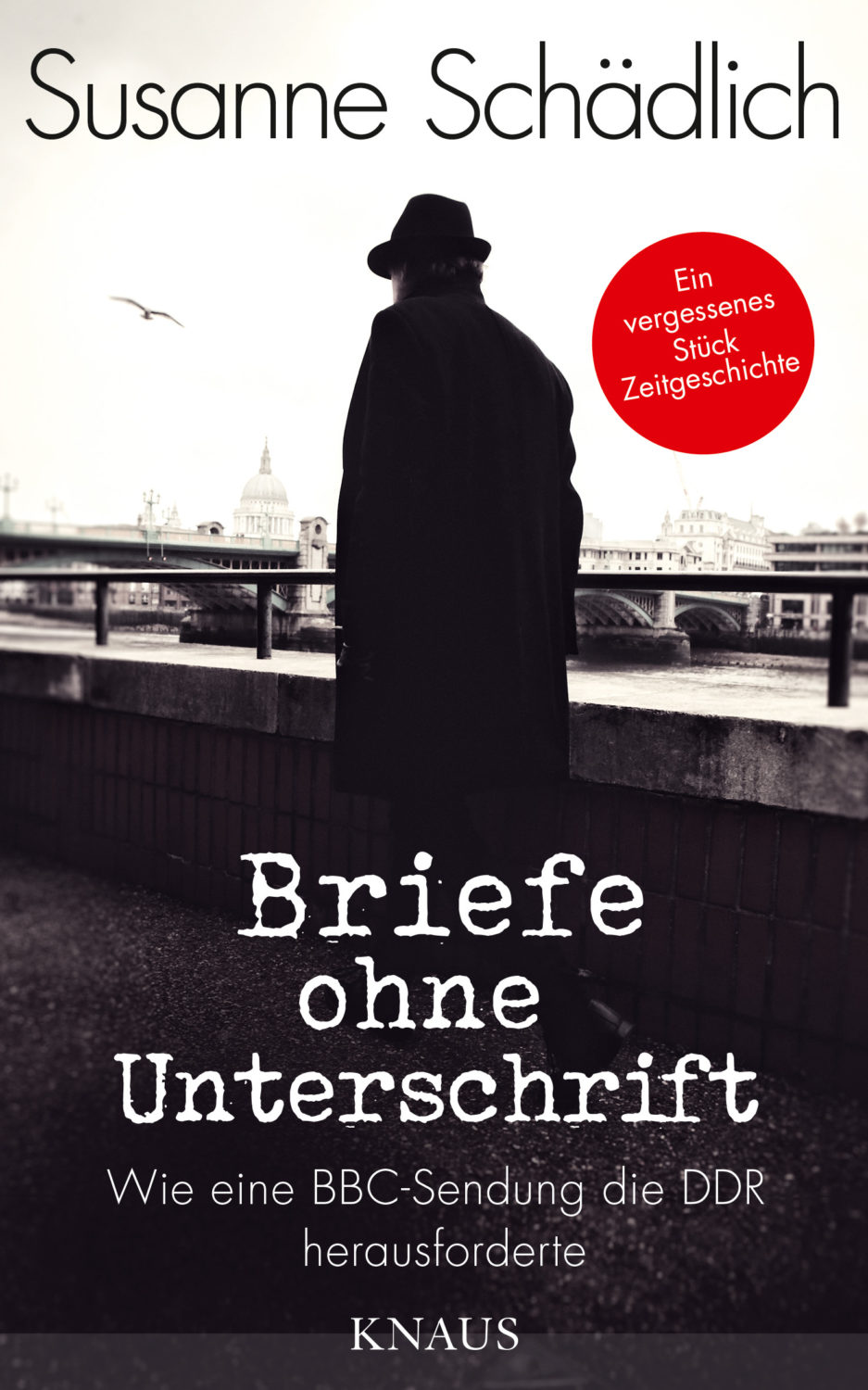

For twenty-five years, a BBC radio programme was required listening for those critical of the East German regime. From the late 1940s until 1974, BBC Radio’s German service broadcast a weekly programme called ‘Briefe ohne Unterschrift’ (‘Unsigned Letters’), aimed at listeners in the German Democratic Republic. Since tuning in to the BBC was ideologically unacceptable in East Germany, would-be letter writers were instructed not to sign their letters. Each Friday, the programme-makers announced a new address in West Berlin where letters could be sent. The programme was extremely popular, and the team behind it received many more letters than they could ever read out. They selected letters with contrasting viewpoints and urged their listeners to consider which ones were closest to the truth. While most letters seem to have been extremely critical of GDR and Soviet Bloc politics, the programme’s coordinator and frontman, Austin Harrison, also gave some airtime to defenders of the regime. Rather than imposing a particular ideology on listeners, he urged them to listen with open minds and compare the different viewpoints being aired.

Susanne Schädlich explores the impact the programme had on listeners, both those who longed for freedom of opinion and expression as well as their opponents, the Stasi and their countless ‘unofficial collaborators’. She quotes extensively from listeners’ letters and from the Stasi’s verbatim records of some of the broadcasts, as well as their surveillance of Austin Harrison and his colleagues on visits to East Germany. This makes for a mosaic of textual fragments and viewpoints that is fascinating and at times nerve-wracking. Schädlich writes engagingly about her own discovery of the material and her hunt for clues, and Unsigned Letters often reads like a novel.

This is a unique book focusing on the opportunities which the BBC provided for East Germans to express their opinions and debate with one another. It is both a fascinating and little-known corner of broadcasting history, and a compelling aspect of East German history. Given the attention which has recently been given to the phenomenon of ‘echo chambers’ in social media and the consequent dangerous narrowing of space for political debate, this book – so passionate about the immense value of the older medium of radio in the hands of a dedicated, idealistic humanist – could not be more timely.

All recommendations from Spring 2017