New Books in German talks with Professor Karen Leeder, Professor of Modern German Literature and Fellow of New College Oxford, about translating the work of Ulrike Almut Sandig.

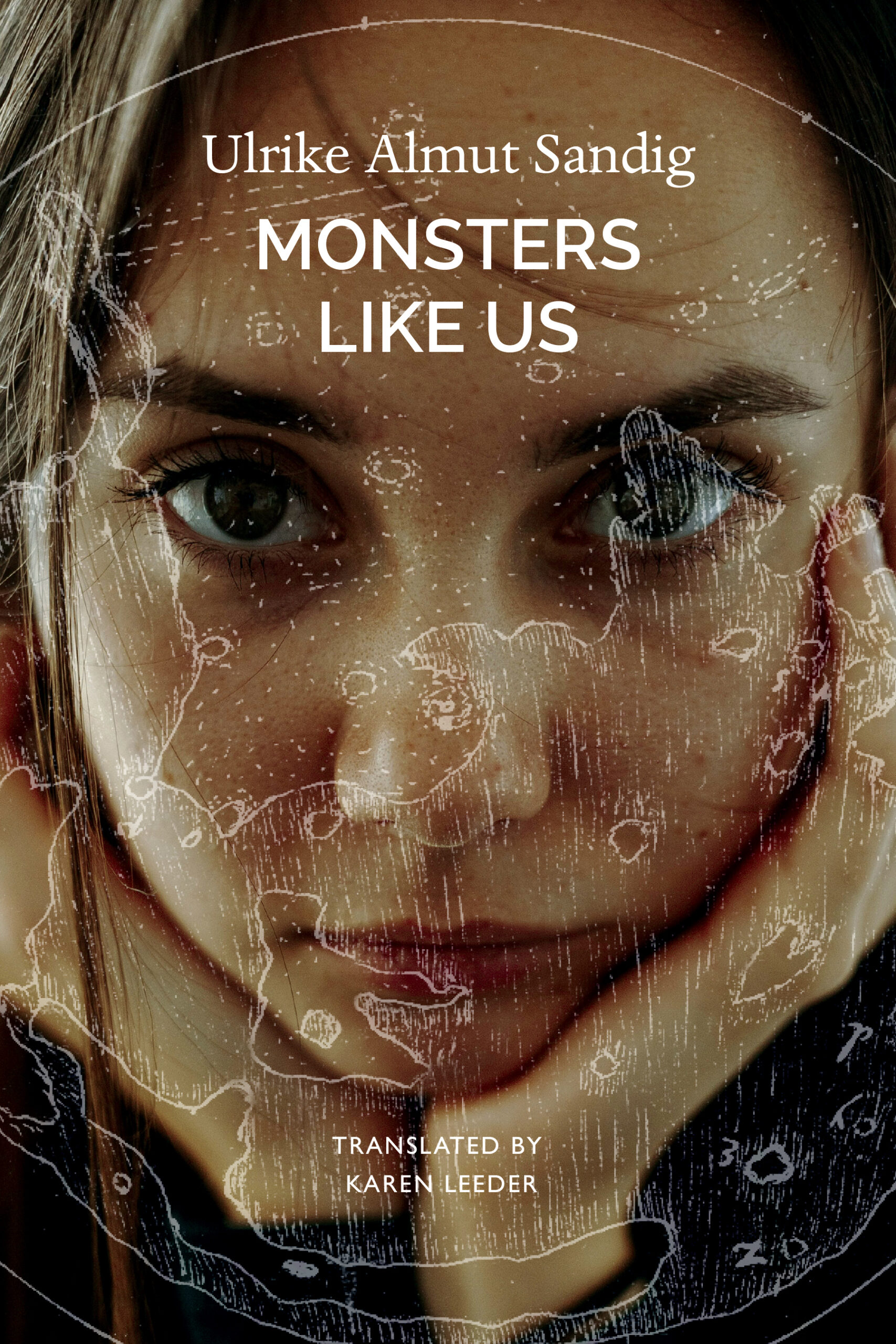

Karen’s translation of Monsters Like Us was published in June 2022 by Seagull Books. Lyrical, tender, at times deeply disturbing, it is a coming-of-age story of two friends growing up in East Germany just before the regime collapses. The book is a nuanced portrait of families and the many forms of abuse that can remain hidden within them. Its characters struggle to come to terms with how the country is beginning to cease to exist. Karen explains how the book is also about “the much more subtle brutalities that go on every day in families … and how people have to find a way through them.”

Monsters Like Us was a New Books in German recommended book, and selected as a favourite by our US jury. You can read the full recommendation here.

Helen Nurse: How did you come to translate Ulrike Almut Sandig’s debut novel Monsters Like Us?

Karen Leeder: Well, I first came across Ulrike Almut Sandig a long time ago. In 2011-12 a fellow translator, Sally-Ann Spencer, was curating a selection of German poetry for a New Zealand literary journal, Sport. It was the guest country that year at the Frankfurt Book Fair and she asked me to find some up-and-coming young German poets to include. I had just come across some of Sandig’s poems in recent ‘the year in poetry’ anthologies and thought they were something special and interesting. And so, I translated her as one of about half a dozen poets. But realised very quickly I wanted to do more so got in touch and we’ve been working together since.

Helen: How did you find the process of translating Monsters Like Us? It is an extraordinary book, but I struggled to sleep after I read it, so I am wondering if you found it traumatic to translate parts of it.

Karen: That is a good question. I had translated her collection Dickicht (2011) which came out in 2018 as Thick of It, published by Seagull. Then another collection (I Am a Field Full of Rapeseed, Give Cover to Deer and Shine Like Thirteen Oil Paintings Laid One on Top of the Other) came out in 2020, so in a way we were used to working together and I felt I understood much about what matters to her: her sense of music, her politics, her sound. She also writes short stories and so there’s always been the idea to do those, but short stories are quite hard for publishers to take on, they’re a very particular and generally rather uncommercial genre. And then she wrote this novel that was a hit in Germany and it was immediately clear that I wanted to do it in English.

I don’t translate a lot of prose generally, although I have done some stories by Michael Krüger, which are delicate, ironic and funny pieces, with long, beautiful, chiselled sentences and some exquisite, otherworldly prose by Raoul Schrott. But here was this massive, traumatic book all of a sudden. I know I felt a pressure to do it justice – and the experiences it tells – also on behalf of the many people who suffer without being heard. But in fact – this is perhaps embarrassing – first of all, I was quite interested in the process, because poems are much more singular, they often have different voices and different problems, and you come up for air after each one; but with this, you’re launching yourself into an entire, quite claustrophobic universe. Actually, in a way, it’s easier because once you hit the sound, once you find it and you have it in your ear, it’s a matter of reconnecting with that every day, whereas poems each have their own voices, some poems can come very quickly, then others can take months to get a rhyme or to get a form. But with this, having that voice in my ear all the time, I found it fascinating and totally absorbing. I really drew close to the characters and their voices. Of course, there are different narrators in this book, and each of them has a different sound. I felt quite bereft after I’d finished the first section narrated by Ruth, and then I lost her and was getting into Viktor and he has a completely different voice again…

“But here was this massive, traumatic book all of a sudden. I know I felt a pressure to do it justice – and the experiences it tells – also on behalf of the many people who suffer without being heard.”

Professor Karen Leeder

Helen: Which suddenly veers off again, when Viktor is in France. And then there’s the presence of Ruth’s Finnish boyfriend, Voitto, too.

Karen: Yes, so there was the question of meeting these different characters and finding their range and their pace, but also throughout the whole book, Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight Sonata’ is there in the background. It comes up explicitly a couple of times, with Ruth, as a pianist, and then there’s the motif of the lunar globe, which the abused boy Viktor holds. But this piece of music underlies it all as a structuring principle and makes sense of the different tempos and the returning riffs. Once I had understood that the novel worked like a piece of music, I knew I could do it. In a sense the fascination with the structural aspects perhaps kept the traumatic ones at arm’s length.

The book got an immediate press reaction in Germany because it deals with sexual abuse and violence, and deals with it in the intimate arena of the family. However (I hope people understand this, it would be important to me that they recognise this), it also deals in a larger sense with violence and coercion at a societal level. The problem with the reception in Germany was that it was focussed in a very particular way but also quickly got caught up in issues of autobiography. The figure of the father shares some aspects of the biography of Ulrike Almut Sandig’s father and his experiences in the GDR, so people made a kind of shortcut and that’s what they wanted to talk about. It was a shame really because the novel is hugely sophisticated and operates constantly at multiple levels.

“Once I had understood that the novel worked like a piece of music, I knew I could do it.”

Professor Karen Leeder

Helen: But the book is also about a radical upheaval in society and there is the threatening presence of the Soviet soldiers too – so there are many layers of violence and fragmentation. Some of the things that happen in the book make it difficult to read. As a mother, I had a very visceral reaction to what happens to the children. Some of the violence and abuse is so casually dropped in at the beginning that you almost don’t notice what is going on. But Viktor’s experiences both as a child and in France are brutal. I’m just wondering, did you need to take a moment or were you able to detach yourself from it?

Karen: I think it’s probably different if you’ve got children or not. So, I’m going to tell you a story. Just after I’d had my daughter, a long time ago, I went to review the film Downfall for the radio, and it was my first kind of job like that after having a child. And in the film, in Hitler’s bunker, Magda Goebbels goes to kill her six children. I was there amongst all these hard-bitten cinema reviewers in this darkened cinema. It was very loud, booming and felt like a bunker, and I was just there with tears running down my face and sobbing, and felt so ridiculous because I was meant to be reviewing it. But I didn’t feel that with this book actually, and I’m trying to think why. No doubt, there is a difference between film and the novel form in the way you are exposed to it. But I am interested in your response. There are two powerful scenes where Viktor erupts into violence, but actually for the most part, the most brutal violence and abuse in the text is not talked about explicitly. It’s always hinted at or suggested, refracted though memory, the failure to comprehend and later also the willingness to suspend disbelief, to tolerate. At a few points the text plays with the reader’s desire, perversely enough, to be sure: “I know what you’re thinking right now. Just be clear and unambiguous! But nothing was clear. Did he come to me every night – or was it just once? Was it really Grandfather – or just a bad dream that I dreamed over and over again?” And you have to remember these are for the most part children remembering. There’s always a sort of veil between what happened and the memories of it. That’s partly what the book is about – also the sense that these things don’t happen “in good families”.

Helen: Yet it clearly happens all the time, and there’s this idea, expressed in the book by Ruth, who says, “If you don’t talk about it, then it hasn’t really happened.” And she also says, “It was no wonder we didn’t understand. We did everything in our power not to hear”.

Karen: Yes, exactly: the text treads a very delicate path between making it clear that things did happen, but also showing that, for all kinds of reasons, that could never be acknowledged in the family; and the child is caught between these two things. I think that for me, as a translator, I was always concerned with the language and finding that delicacy, not being too ‘eindeutig’, not being too obvious, unambiguous, that there was a musicality, a precision and a beauty even when the text was talking about the most horrific things.

Helen: Yes, it’s extraordinarily beautiful and that’s why I think it becomes ever more shocking as you read on. It’s done so tenderly. There’s a tendency with literature that deals with violence or abuse to completely overdo it. I sometimes think these writers have never experienced anything like that, because in reality trauma numbs. When you talk about the ‘veiling’, that’s a natural reaction to trauma, i.e., if I pretend it didn’t happen to myself, then it really didn’t happen, but it inevitably resurfaces and then has to be suppressed again. Viktor and Ruth’s reactions to the abuse they experience are so different.

Karen: It’s a very capacious book, I mean, it takes on a lot of things because it’s also a story about art and it’s in that tradition of artist stories as well, and about the role art can play. It talks about ecological awareness, about a landscape under threat and the people who are trying to defend it. There is also a fascinating aspect of the work which I would hate to be missed and that is the story of growing up in East Germany. It’s a coming-of-age story, but it’s set against the backdrop of a country that ceases to exist, and what happens to the people as that country disappears and is literally swallowed up. One of the very powerful images in the text is when Ruth (who was brought up in East Germany as a child) goes back as an adult to see her village, which has literally disappeared into an abyss. And so it’s about coming to terms with what lies in the past and your access to it.

“There is also a fascinating aspect of the work which I would hate to be missed and that is the story of growing up in East Germany.”

Professor Karen Leeder

Helen: And also your childhood, the visual reminder of it has been taken away, hasn’t it?

Karen: Yes, the landscape is gone and all the coordinates that gave life meaning as a child are gone: the apple trees in Ruth’s garden, the corn fields behind Viktor’s new build house. What is more, reaching back to these things has to be done through the fact of abuse and all the complications and distortions and refractions that brings. It’s also about the much more subtle brutalities that go on every day in families and in long marriages, and the difficulties, the meannesses, the anger and the resentments, and how people have to find a way through them. I’m thinking about the relationship between various couples in this book – quite apart from the central abusive relationships.

Helen: The reaction of Ruth’s mother is interesting, isn’t it? Did she hear Ruth, when she says her grandpa is a vampire, because straight afterwards they go to visit him. There are all these tangled feelings – a duty to parents, having to look after a man who is ill, but then taking a child back into the family home where it happened. Is she turning a blind eye, or has she genuinely no idea what’s happening? There are so many questions.

Karen: Yes, how interesting, because the first thing I said to Ulrike after I translated it was, does the mother know? Because I think the book leaves it open, it doesn’t really tell you. And this is one of the clevernesses, I think, because a lot of people in this book are alone and struggling with their own background, their own hurt.

Helen: Yes, Ruth’s mother is struggling with her marriage as well, she’s trying to escape that, she’s trying to look after her father, she’s trying to protect her children. There’s so much going on there.

Karen: Yes, it is worth re-reading and multiple things come out, it’s very layered and very subtle. But I think it leaves multiple levels open, for all the stories here, about how much people knew, consciously or not.

In the story of Viktor in France it’s very clear that Madame, the wife, knew, even before she sees her husband abusing their son. And so, it is a book that asks about what stories we tell ourselves to allow us to continue. And it’s clear that she will continue. She says she knows and it’s only one version of the story, and perhaps not even the worst version of the story…. which is horrific really. It’s about the kind of lies that allow us to keep on living and all the harm they do.

It’s also the story of a nation trying to come to terms with its past and find its identity. You can see it in the background: from the relationship with the Soviet troops, to the rise of the New Right after 1989, the hopelessness, the drugs etc. For example, I remember talking about this when I was translating it, Viktor is going to France as an au pair and we spend a long time with him on a train journey on his way there and I was wondering what’s this about? In his compartment there are two young girls who are going to be “waitresses” and it’s clear that actually they’re going to go and do sex work. In the same compartment there’s a Polish surgeon who’s going to do some building work and originally I could not understand. Sandig explained that in the economic uncertainty just after the Wende, professional people could earn more travelling to do a season of building work in the summer than they could in their own field. So details like this paint the backdrop of the economic necessities that drive people in different directions and a moment in time when all was insecure. All these are people struggling to come to terms with the new social system and the economic reality of that system.

“All these are people struggling to come to terms with the new social system and the economic reality of that system.”

Professor Karen Leeder

Helen: They also suffer a loss of standing. Because in the DDR, if you were in the established system as an artist, you were quite well anchored and respected. It must have been really hard for poets and writers to come into a system that was much more commercially driven. And to cope with the loss of status, and questions around the arts and the importance of them, as they are accorded a different importance in the West.

Karen: Yes, though Sandig of course was too young to experience that. But you’re right, for many established writers in East Germany, there was a real shock to the system in the commercial world where the role of the writer is so different. A popular image at the time talked about a ‘fall from the pedestal’. In a totalitarian regime, the writer takes on a special role, to articulate the truth for people who cannot; a truth that isn’t there in the media, the politically-sponsored media, so that literature becomes an alternative public sphere: a place for a special kind of truth-telling that also incidentally has a detrimental effect on literature itself I think. There’s this idea of censorship as a mother of metaphor, that you learn to operate under pressure and develop different strategies. And there’s a truth to that too: that writers developed a very fine way of writing that managed to say things in a very delicate way, but also that readers developed a very high sensitivity to reading between the lines.

Helen: Thank you, Karen, for taking the time to share your work with us.

Professor Karen Leeder is a writer, translator and leading British scholar of German culture. She is professor of Modern German Literature in the University of Oxford and researches modern German literature including the literature of the former East Germany.

Karen’s translations of Ulrike Almut Sandig are published by Seagull and can be found here: https://www.seagullbooks.org/monsters-like-us/; https://www.seagullbooks.org/i-am-a-field-full-of-rapeseed-give-cover-to-deer-and-shine-like-thirteen-oil-paintings-laid-one-on-top-of-the-other/#details; https://www.seagullbooks.org/thick-of-it-pb/

Karen’s translation of Michael Krüger can be found here: https://www.seagullbooks.org/our-authors/k/michael-kruger/

Karen’s translation of Raoul Schrott can be found here: https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/distributed/S/bo28484369.html