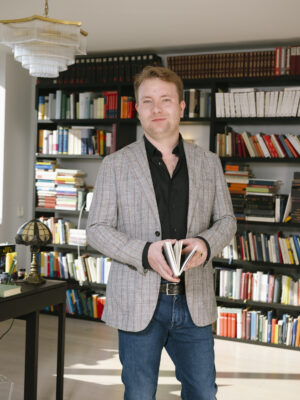

Gwendoline Choi interviews Dr Charlotte Ryland, Director of the Translation Exchange at The Queen’s College, Oxford University. Charlotte is also Director of the Stephen Spender Trust (SST), a charity that promotes language learning and literary translation. Through both organisations she aims to engage people of all ages and backgrounds in creative translation, and to increase the numbers learning languages across the UK.

GC: Hi Charlotte, thank you for your time! Can you tell me more about the Translation Exchange you founded at Queen’s, Oxford?

CR: The motivation for setting up the Translation Exchange came from my experience of outreach work with schools when I was a lecturer at The Queen’s College, Oxford. During that time I was also Editor of New Books in German, which introduced me to the world of literary translation. I loved how collaborative and interactive the literary translation scene was becoming, and I started to think about how I could bring this together with the teaching of Modern Languages in schools, where numbers were already in major decline.

Regardless of linguistic background or experience, if you get a group of people translating in a room together, it generates so much positive energy, and generates such interesting conversations about language.

Charlotte Ryland

When I was at NBG, I set up the Emerging Translators Programme, which was a way of supporting and networking emerging translators, as well as generating sample translations for NBG-nominated books. Shaun Whiteside and I held day-long translation workshops as part of this programme, and these really showed me the creative potential of collaborative translation. Regardless of linguistic background or experience, if you get a group of people translating in a room together, it generates so much positive energy, and generates such interesting conversations about language. Inspired by this, I started to run translation workshops as part of my schools outreach in Oxford. That’s where the idea for the Translation Exchange came from, which I founded at Queen’s College in 2018.

The Translation exchange focuses on energising public support for languages and international culture as well as working directly with schools. Our public-facing work includes regular events both online and in Oxford, often involving international writers and translators, alongside our termly International Book Clubs for adults and young people.

There’s been a real shift in how translation has been viewed in academia. It’s now a widespread area of research and form of critical practice, the latter of which was the aim of this year’s Visiting Fellowship. From the outset, one of the things I wanted to do with the Exchange was to create residencies which would enable translators and writers to work together in person and to co-host events. We started with short 2-3 week residencies, but I wanted to do something more sustained and to integrate them more into the University. Oxford had never had a translator as a Visiting Fellow before, so it was particularly exciting to gain funding for Polly Barton to be this year’s Visiting Fellow at TORCH (The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities). We’ve been able to highlight the craft of translation through a major programme of close to 20 public events.

To further explore this idea of outreach, how can we encourage more school pupils to take up Modern Languages? There has been a significant decline in languages uptake and in the number of language teachers in the UK for a long time, including in German. What are some of the factors involved in increasing German uptake?

In my view, we’re not currently showing young people how exciting it is to be a linguist while they’re in the classroom. We talk about their possible futures a lot – that you might be able to earn more, or travel – but these arguments are too distant for the younger age-groups. Instead, we need to show young people how exciting it is to engage with other languages and cultures, and to do this we need to foreground culture and creativity in their learning experience.

…pupils often describe our workshops and resources as making language-learning feel ‘important’.

Charlotte Ryland

What we know from our creative translation programmes is that from a young age, children can engage with literary texts in another language if they are carefully scaffolded. These texts introduce relevant topics into the classroom, too – quickly moving beyond learning colours, or describing pets. As a result, pupils often describe our workshops and resources as making language-learning feel ‘important’. Creative translation levels the playing field, because through glossaries and other resources it enables pupils of all abilities to engage in the same activity. Finally, the teachers’ enjoyment of creative translation is key to our advocacy work. Enthusing and inspiring teachers means that their enjoyment is more likely to be passed on to their pupils.

Are there any stumbling blocks you encountered when doing your outreach work?

One of our first activities at the Exchange was to train university students to design and deliver translation workshops in schools: our Creative Translation Ambassadors. We partnered with the Stephen Spender Trust, as they had experience training translators to deliver workshops in schools. That side of things went well, but what I hadn’t anticipated was how much labour and admin was involved when running projects with schools. In general, anything that takes students off timetable or requires extra time of teachers becomes very difficult to execute, particularly in schools with low uptake of languages.

As a result, we started planning the Anthea Bell Prize, a free to enter translation competition for schools which is inspired by the life and work of the great translator Anthea Bell. We developed virtual resources for teachers, so that they could deliver translation workshops to their pupils. This greatly increased our reach and was a really effective use of our resources. The pandemic started while we were planning the prize, and suddenly this form of virtual delivery was the only one available. So when we launched the Prize in September 2020, teachers were already used to online delivery. Our initial aim was to reach 50 schools, but ultimately over 500 teachers registered in our first year. We’ve just completed year three, with over 15,000 young people taking part.

How has outreach work changed over the years?

I’ve found that undergraduate participation in schools outreach has often missed opportunities. The standard has been for undergraduates to take part in Q&A panels at university outreach events, for example. But for the age we’re focusing on (11-14), it is a stretch to expect these pupils to know what questions to ask. Instead, we are seeing increasingly that good outreach requires undergraduates to collaborate with school pupils, all working together on a project. This breaks down any barriers and makes the undergraduates seem accessible.

For me, Creative Translation is a microcosm of a languages degree – you acquire language knowledge, you learn more about culture, you get to engage with contemporary texts, and you have to think critically.

Charlotte Ryland

If we want to enable pupils to imagine their future selves at university, then undergraduate outreach has to make pupils feel: ‘that could be me’. Translation workshops also forge a clear link between what happens at university and at school. For me, Creative Translation is a microcosm of a languages degree – you acquire language knowledge, you learn more about culture, you get to engage with contemporary texts, and you have to think critically.

I know you’re passionate about widening access at university, too. How can we attract and retain Modern Language students at the university level, given decreasing interest?

I think there’s a huge messaging problem in languages advocacy. The enormous benefits of a languages degree aren’t communicated well. I think universities need to reach a closer consensus on what it means to study languages in the 21st century. Advocacy that places emphasis on intercultural engagement is more effective, and it’s important to emphasise that all the skills you gain by learning languages aren’t limited to the linguistic alone.

I think talking to parents and carers as well as students and teachers is critical. We have a new project called ‘Think Like a Linguist’, in partnership with Widening Participation at Cambridge University, the Stephen Spender Trust, and the Modern Languages Faculties at Oxford and Cambridge. As part of the project, we are running a series of workshops for Year 8 pupils, and involving parents and carers at key moments.

I know you’ve had a longstanding research interest in Paul Celan. Can you speak a bit about how your relationship with Celan’s work has changed over the years?

I started to work on Celan initially because I was interested in post-Holocaust literature. I then became interested in his translations, which enabled me to bring my German, French and English together, and to broaden out from my forensic focus on his poetry. That’s how I got into translation in practice and theory, which in turn led me to New Books in German.

Al you need is a poem to have a rich cultural and linguistic experience!

Charlotte Ryland

During my PhD, I spent four years reading poetry really carefully. I learnt how thrilling it was to have the time to read so closely, and to look at what happens when texts transition between languages. I think this fed into what I’m doing now, as poetry is central to our outreach programmes. All you need is a poem to have a rich cultural and linguistic experience!

You’ve used the term ‘portfolio career’ to describe your own path. Has there been a career move that has really surprised you?

I think my career moves felt strange to me at the time, but looking at where I am now, there’s been a really clear thread throughout my career: that I love languages, and I want other people to be able to have the positive experience that I have had. I think what might be more surprising is what I didn’t become: a teacher. I have an inherent interest in teaching and education in many respects, and I enjoy classroom interaction a lot. I think everything that I have done has related to this interest, and it feels like a huge privilege to pursue this interest while working with so many great teachers, translators, academics and young people.

We like to finish our interviews by asking people what they’re looking forward to reading. Are there any books that have caught your eye?

I’m really looking forward to reading My Soul Twin by Nino Haratischvili, translated by Charlotte Collins. I read the German novel years ago, for New Books in German, and absolutely loved it, so I can’t wait to experience it again in Charlotte’s words.

Thank you Charlotte! Incidentally, readers of can find out more about Charlotte Collins’ experience of translating My Soul Twin in this interview with New Books in German.

Charlotte Ryland is Director of the Stephen Spender Trust and founding Director of the Queen’s College Translation Exchange (Oxford), organisations dedicated to promoting language-learning, multilingualism and translation. In both of these roles she aims to engage people of all ages and backgrounds in literary translation, and to bring creative translation activities into UK schools. Until 2019 Charlotte ran New Books in German.

Gwen Choi completed an undergraduate degree in Philosophy and German at the University of St Andrews. She is currently a postgraduate student at the University of Oxford.